Covid-19 fallout: The impact on education in India

The Covid-induced lockdown ravaged the education system with schools closing down and online learning nowhere near effective

Do the math

- Over 1.5 million schools across India closed down due to the pandemic A switch to large-scale digital education is not possible now.

- Only 24 per cent house-holds have access to the internet, according to a 2019 government survey.

- In rural India, the numbers are far lower, with only 4 per cent households having access The education ministry’s budget for digital e-learning was slashed to Rs 469 crore in 2020-21—the year Covid struck—from Rs 604 crore the previous year

Shubham Gupta is a first-year student of BCom (Honours) in Delhi's Hansraj College. Yet the 18-year-old hasn't set foot on campus even once since he took admission in September. He has taken a virtual tour of the college and has been taking lessons through his mobile phone and iPad. And Shubham isn't alone in this. That's how the batch of 2020-the Covid-19 generation-has been experiencing institutional education in a world disrupted by an unprecedented pandemic. Because of this, 47 per cent students have decided against migrating to another city for higher education, revealed a study titled the 'Big Qs Student Survey'. Fifty per cent respondents have also abandoned plans to pursue higher education abroad.

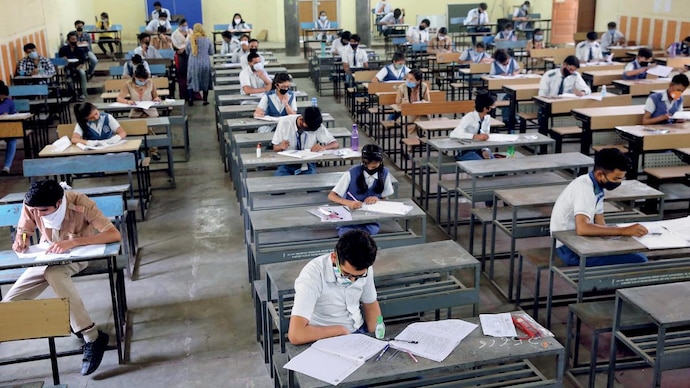

Over 2,000 kilometres away from the national capital, in Assam's Barpeta district, Nibha Choudhury, a 41-year-old teacher in the government-aided Finguagarh High School, had an extended holiday between the last week of March-when the country went into the national lockdown-and September. The school authorities tried to conduct online classes, but less than five per cent of the students had reliable and consistent internet access. "We sent out lessons and homework to the handful of students who had smartphones and internet connections. They helped some other students, but it was by no stretch of the imagination a substitute for classroom teaching," says Choudhury. In the past two months, she has been slogging extra hours to compensate for the classroom hours her students lost during the lockdown. It's not easy to impart education in segregated classes where the prime focus remains maintaining Covid protocols.

While students in Assam and several other states have gradually returned to schools and colleges, their counterparts in states like Delhi are still confined to homes, spending long hours online, leading to concerns over physical health and stress triggered due to the prolonged use of electronic devices. The education ecosystem of India, already weighed down by myriad issues such as school dropouts, learning deficiencies, teacher absenteeism, gender disparity and lack of infrastructure, now faces yet another big challenge-the widening digital divide. Even in the national capital, when government schools started online classes during the lockdown, the attendance hovered between "25 and 30 per cent".

According to UNICEF, the Covid-19 pandemic has battered education systems around the world, affecting close to 90 per cent of the world's student population. In India, over 1.5 million schools closed down due to the pandemic, affecting 286 million children from pre-primary to secondary levels. This adds to the 6 million girls and boys who were already out of school prior to Covid-19. This disruption in education has severe economic implications too. A World Bank report, 'Beaten or Broken: Informality and Covid-19 in South Asia', has quantified the impact of school closures in monetary terms-India is estimated to lose $440 billion (Rs 32.3 lakh crore) in possible future earnings.

To fight back the disruption and damage, educational institutes across the country embraced the digital mode of education as a solution to fill the void left by classroom teaching. With this, the hitherto peripheral digital education in India came centrestage and is now increasingly getting integrated into the mainstream. The National Education Policy, released by the Union government in July, has also emphasised the importance of online education, blended with the traditional mode.

A KPMG and Google study, done before the Covid-19 outbreak, estimated that the online education market in India was set to grow to $1.96 billion (Rs 14,836 crore), with 9.6 million users by 2021, up from $247 million (Rs 1,870 crore) and 1.6 million users in 2016. The coronavirus-induced lockdown further propelled the market demand for EduTech players. India has now emerged as the second biggest market for massive open online course (MOOC) in the world after the US.

While the Covid-19 pandemic has made online education the buzzword, a recent report by the global education network Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) says that the Indian internet infrastructure is still far from ready to support the shift. Only 24 per cent households have access to the internet, according to a 2019 government survey. In rural India, the numbers are far lower, with only 4 per cent households having access. A 2018 NITI Aayog report revealed that 55,000 villages in India did not have mobile network coverage. A 2017-18 survey by the ministry of rural development found that more than 36 per cent of schools in India operated without electricity. The emphasis on technology-driven education is also alienating many children from the underprivileged sections, preventing them from continuing their studies. Even other stakeholders are struggling. Teachers are not always trained and equipped to transition to online teaching.

As e-learning becomes the "new normal", the authorities have been taking steps to make digitisation of education accessible and affordable for all. The Union government is banking hugely on the Bharatnet project, which aims to provide broadband to 250,000 gram panchayats in the country through optic fibre to improve connectivity. Broadband connectivity in gram panchayats is expected to help rural schools provide online education to students who do not have internet access at home. Besides building the digital infrastructure, training has to be given to the teachers to use the system to provide authentic and seamless education to the students. Successful delivery of education is also in question because learning in colleges varies from that in schools. Digital education cannot be applied the same way at every level.

If the Indian education system has to transit to online learning without creating a digital divide, the Centre and state governments must raise the spending on education to at least 6 per cent of GDP. At present, central and state allocations to the sector is less than 3 per cent. Ironically, the education ministry's budget for digital e-learning was slashed to Rs 469 crore in 2020-21-the year Covid struck-from Rs 604 crore the previous year.

CASE STUDY

"We had to change the exam system to suit the online mode"

RITU WADHWA, 40: Asst professor, Amity Business School

PRITOM BARMAN, 23: MBA (Finance), Amity University, Noida

For Pritom Barman, the shift to online learning came with its own set of challenges. Pursuing an MBA (Finance) from Amity Business School, Amity University Noida campus , Uttar Pradesh, Barman had to leave the residential campus and shift back to his hometown in Arunachal Pradesh when the country went into a complete lockdown on March 24. He left some four days before as did most other students.

The Amity Business School, Amity University, shut the campus on March 20 and all students and teachers were informed about online classes. For Barman, who used to depend on class notes and books in the college library, it was a tough call. Back at his family home in Naharlagun, in the Pamum Pare district of Arunachal Pradesh, he found himself handicapped, with no physical access to the library. "We attended the lectures online and studied the notes sent by the faculty," he says.

Online classes started on March 23 and all the staff were trained by the in-house IT department on how to take classes on MS Teams. Ritu Wadhwa, assistant professor, Amity Business School, says, "There were minor teething problems on the first day, but from then on it was smooth. We conducted exams by changing the structure and question papers to suit the online mode."

Barman had to overcome several limitations to keep pace with his batch due to the intermittent internet connectivity in Arunachal. "It was challenging as everything was happening on MS Teams and e-mails. The connection fluctuated between 0.5 Kbps and 80 Kbps and even attending lectures was a tough ask."

At times, it was so bad he had to go out of the house and join the classes on his phone. "I had to sit on the roadside and attend lectures," says Barman. And during his mid-term test, he had to shift to a friend's place as the connection was better there. He later gave all his exams from there.

Wadhwa says, "It is mandatory for students to mark attendance when logging in for lectures and Barman had a unique problem-he couldn't due to the bad connectivity. But he still managed to attend all lectures and upload all assignments, at times from a cyber cafe."

Both Barman's batchmates and the faculty helped him a lot. His friends made a WhatsApp group where they sent all the slides shared by the faculty. He says, "If I missed a class, I would go through the recording of the lecture available on MS Teams. The faculty was always active to clear any doubts. The best part was the LMS (learning management system) set up by the university where students could get all the extra study material, class notes and journals."