Philly artist wins $100K craft prize for her work remembering Black ancestors

Adebunmi Gbadebo makes work from materials sourced directly from her enslaved ancestors.

Listen 1:54

Artist Adebunmi Gbadebo stands with her piece “Remains, piece of Balcony Baluster, 1848,” featuring salvaged pieces of the historic McCord House in Columbia, South Carolina, which were carved by the artist’s enslaved ancestors. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The Philadelphia-based artist Adebunmi Gbadebo has won a major craft prize from the Maxwell/Hanrahan Foundation in the San Francisco Bay area, to the tune of $100,000.

“It’s a blessing just getting the award,” said Gbadebo, 31. “But especially, as an artist, awards like this create more stability. I really equate stability to longevity in an artist’s career.”

Gbadebo’s work is currently on view at the Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, as part of the group exhibition “Songs for Ritual and Remembrance.”

She also has work in a major traveling exhibition, “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” in which her pieces accompany stoneware made by enslaved Black artisans of the early 19th century. “Hear Me Now” opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and is now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Later this summer it will go to the University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor.

“Adebunmi Gbadebo’s use of culturally and historically imbued materials such as indigo dye, soil hand-dug from plantations and human Black hair is a powerful investigation of the complexities between land, matter and memory on various sites of slavery,” the foundation said in a statement.

Unlike many craft artists, Gbadebo does not specialize in a particular medium. She moves between ceramics, paper making, fiber, and wood. The power of her art is in how the materials are sourced: Most can be traced directly to her ancestors.

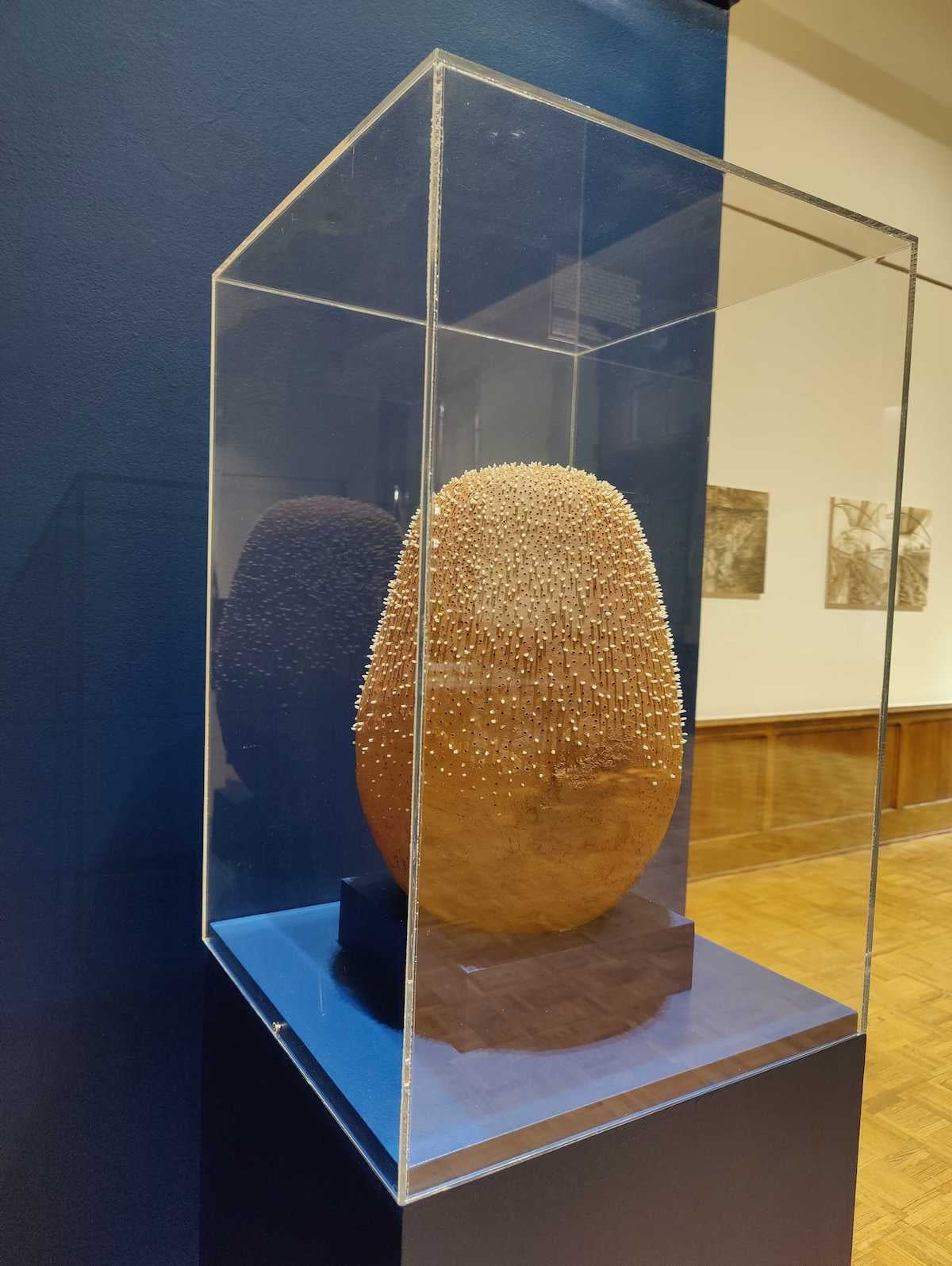

The exhibition “Songs for Ritual and Remembrance” features a ceramic vessel made from the soil of the South Carolina plantation cemetery where her enslaved ancestors are buried. It is spiked with grains of Carolina Gold rice, the crop her ancestors would have tended.

There is a set of rotted wooden balcony balustrades that were carved by her enslaved ancestors as they built the McCord House in Columbia, now a registered historic landmark. Gbadebo salvaged them during a renovation.

A tapestry made from pulp and dyed indigo, a color derived from the cash crop at the True Blue Plantation where her ancestors were enslaved, is woven with strands of Black hair.

“What I will say is, my use of Black hair has been a constant,” Gbadebo said. “It is our body. It starts not from an art store, but from these intimate moments: A woman in her bathroom cutting her hair, or a barber giving a kid his first haircut. These private and public Black spaces.”

“Songs for Ritual and Remembrance” also features work by artists Ken Lum, Mary Ann Peters, and Guadalupe Maravilla. They each investigate histories of trauma and resilience.

Some of those histories are personal to the artist, like Gbadebo and Maravilla, who is a native of El Salvador. Maravilla makes found-object sculptures using materials scavenged from border crossing territories, like the one he traversed as an unaccompanied 8-year-old boy crossing the border into Texas in 1984.

Other pieces in the show are based on researched histories, like Peters’ pieces related to 19th century Syrian women working in silk factories who successfully pushed the French government of the time to increase wages and improve working conditions.

Curator Emily Zimmerman assembled artists whose work uplifts suppressed historic narratives and community memory.

“One of the other themes of the exhibition, after we come out of the pandemic, is to talk about: How does one heal from traumas?” Zimmerman said. “We’ve been through a mass traumatic event, and to start to not only reckon with histories that have not been properly acknowledged, but also our recent past.”

Gbadebo, originally from Maplewood, N.J., relocated to Philadelphia in January 2021 to take what was supposed to be a three-month artist residency at the Clay Studio in Kensington.

“That three-month guest residency turned into a five year-long residency,” she said. “So I’m here for good now.”

Part of what makes Gbadebo’s work extraordinary is the relationship it represents with her ancestors. Not only does she know their names and where they lived more than 150 years ago, but she is able to visit them at the cemetery. She said she goes to True Blue cemetery, near Fort Motte, South Carolina, a few times a year, sometimes to help maintain the land, other times to get materials for her artwork.

“My ancestors claimed the woodlands, the part of the plantations that weren’t viable,” she said. “They claimed those woodlands and buried their loved ones, and after emancipation they continued to bury there. My family never severed, because they continued to bury and visit loved ones.”

The Black community that remained in the area of True Blue Plantation and neighboring plantations, like the Singleton and Lang Syne Plantations, built the Old Jerusalem Church in 1890 near the cemetery, and continues to use it to this day. Gbadebo acquired old pews from that church and hauled them to Philadelphia, where they are now on view in the exhibition.

She says her family’s burial soil is full of life. That’s not a metaphor: If she does not fire her ceramic vessels quickly, they will sprout.

“I take the soil, make it into moldable clay, build a vessel,” she explained. “If I cover it in plastic, which is creating a lot of humidity, it’ll start growing plant life.”

“Songs for Ritual and Remembrance” will be on view until September 17.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.