ADAMS — It was on Sunday, Nov. 2, 1851, the elephant Columbus — injured days earlier when he plunged through the wooden Center Street bridge in Adams — took his last breath and died in a barn on the side of Old Stockbridge Road in Lenox.

"I saw him dying on Friday," author Catherine Sedgwick wrote to her niece, Katherine Minot, that same day. "He lay quiet, looking dreamily around, his proboscis curled up, without a struggle or movement, seeming to express the submission of the mightiest thing on earth to a stern, inexorable omnipotent Fate."

According to reports at the time, the elephant's owner, James Raymond, in anticipation of its death, sold the remains to The Lyceum of Natural History, a student club at Williams College. The club had intended to stuff the animal and add it to its collection in Jackson Hall, but unable to secure a taxidermist able to handle it, they decided to bury the elephant and claim its skeleton at a later date.

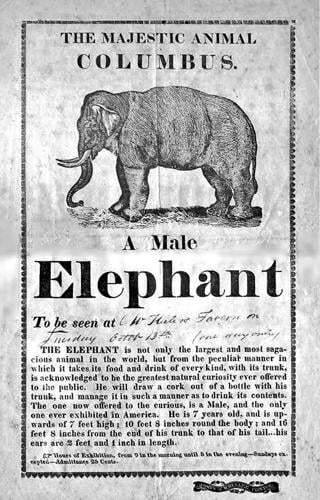

The day after his death, Columbus, billed as the "largest [elephant] in America, weighing 10,730 pounds," was buried on the property of Cortlandt Field Bishop. Over the last 168 years, the story of the elephant's death faded into local lore and the location of his final resting place shrouded in mystery.

But now, Leo Mahoney, of Lenox, believes he's solved that mystery. He'll present his findings, along with a history of the famed accident and death of Columbus, at the Adams Historical Society's annual meeting, 3 p.m., Sunday, May 5, in the Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Hall at the Adams Free Library.

"I've been looking into Columbus for at least 10 years now," Mahoney, a filmmaker and station manager of Community Television for the Southern Berkshires, said during a recent phone interview. "I grew up in Lenox. As kids, we always heard the story of Columbus and that he was buried in our own backyards. Turns out, that wasn't too far fetched."

But researching the story of the famed elephant hasn't been easy.

"It's tough to find two newspaper articles that say the same thing," he said.

The death of Columbus was carried by newspapers around the country, especially since Raymond planned to sue the town of Adams for damages. The New York Times reported that Columbus, "who has tramped, and pretty much been seen all over this continent any of these last 20 years," was 100 years old and valued at $12,000. A paper out of Daneville, Vt. reported his value at $15,000.

Even the identity of Columbus is in question. Raymond claimed the animal was the original, arriving in 1818. But that is unlikely, as the elephant known as Columbus reportedly died in 1829, with his skeleton being sold to a Philadelphia museum. With no expected truth in advertising, it wasn't unusual for menagerie owners to change the names of their animals or their histories. One elephant owned by Raymond was known as Timour, but its name was changed to Hannibal after a few years. It is suspected that the Columbus that died in Lenox, was only a few decades old and was known previously as Hannibal or Mogul.

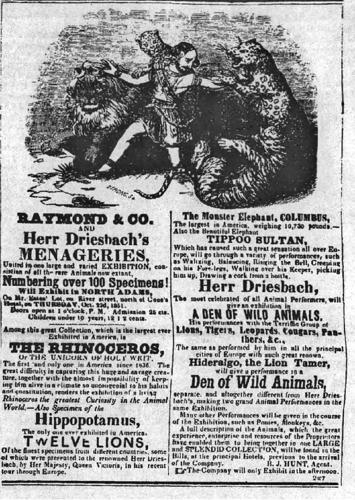

There are a few facts that are known for certain, Mahoney said. It's known that Raymond & Co.'s and Herr Driesbach's Menageries stopped in North Adams on Oct. 24, 1851. From there, the menageries made their way through Adams, en route to their next performance. As the parade of animals approached the wooden bridge crossing the Hoosic River, Columbus began to protest and had to be cajoled and prodded across it. As the great animal made its way across, the bridge gave way and Columbus plummeted into the riverbed below.

"It's a really sad story," Mahoney said. "The newspaper covering the story at the time, said it took them some time to get him up from the riverbed. He seemed to be alright, so they got back on the road and continued to make their way to Stockbridge. It's about a 27-mile walk. At mile 23, that's when he fell."

From there, it's known Columbus spent several days in a barn not too far off the road, where hundreds of people came to view the elephant. What happened to him after his death, is another story.

"Getting two stories to line up is tough," he said. "Some stories say he was buried. Other stories say he was cremated. There's a legend that he's buried under the pitcher's mound at Wahconah Park. There's another story that three elephants were buried in Clapp Park after they died in a train derailment.

"What everybody does agree on is that he was 10,000 pounds and that he got to Lenox. There was no coverage the next day. The menageries were supposed to stop in Pittsfield, but it appears that because of what happened to Columbus they skipped Pittsfield."

Newspaper reports at the time that did report Columbus was buried did not say where.

"The key to the whole story was Catherine Sedgwick's letter," Mahoney said. "She says the elephant reminded her of a dying gladiator. But besides it being a beautiful letter, she named the property where he died. Sure enough, in my research, I was pretty close."

With help from the Lenox Library and the Lenox Historical Society, he was able to locate the barn on maps from the time period.

"Seeing that he weighed 5 tons and there was a lack of motorized tractors at the time, I can't see them dragging the carcass very far. He was buried pretty much where he died," he said.

After the elephant's demise, Raymond, a renowned menagerie owner, who leased his exotic animals to every traveling animal show in the country, sued the town of Adams for $20,000, claiming the bridge was not properly maintained, thus resulting in his star's death. The town countered with its own lawsuit, asking for damages for the broken bridge. The town claimed that it could not be expected to maintain a bridge capable of bearing the weight of an elephant.

"The case was in court for 12 years and went all the way to the state Supreme Court," Mahoney said. Some reports say the case was settled out of court for $1,500.

It's also known that Williams College never claimed the elephant's bones. An attempt was made by the Lyceum in 1857, but the elephant had yet to fully decompose.

"They did exhume him, but within the first few shovel fulls of dirt, the smell was very nauseating. They planned to go back in another five years," he said. "There were two other attempts, one in 1951 and one in 1967. Both times the students were ill prepared. One time they didn't have the proper tools. The other time, they didn't have permission and were chased off the land."

One attempt included a water dowser from Canaan, N.Y., who, armed with dowsing equipment and a baby elephant's skull, claimed to find the grave site within six minutes of stepping on the property.

Mahoney said he hopes to use a more scientific approach to locating Columbus' final resting place: ground penetrating radar. The technology was recently used confirm the location of a long lost graveyard on October Mountain. Those efforts were recorded in "The Bone Finder: Tracking the Dead," a documentary directed by Mahoney in 2017.

"We know the technology works," he said.

Unfortunately, for the filmmaker, the goal of finishing his research and an ongoing documentary doesn't seem to be in the near future. The site in question is part of a private estate and the owner isn't keen on disturbing the land. For now, Mahoney plans to keep researching Columbus and sharing his story.

"It's a story people love to hear," he said.