Introduction

In China's martial culture, tigers have been, since ancient times, a symbol of audacity, courage and dedication in combat. From the late 18th to early 20th centuries, among European missionaries and diplomats who visited China, we found descriptions and references to warriors wearing tiger skins or uniforms that mimic the fur and shape of this animal.

These early references recreate a romantic image of China, and would significantly influence the exotic image that Europeans would develop from the country and, more specifically, from the savage and bloodthirsty indigenous warrior. However, this image would change radically after the Opium Wars, passing from admiration to mockery.

Although some raise doubts about the veracity of these descriptions, wondering if these warriors actually existed, or whether they were simply isolated individuals and not a properly formed military corps, it seems that the "Tigers of War" did actually exist as an infantry contingent during the Qīng 清 dynasty. It was a téngpáiyíng 藤牌營 battalion, this is, soldiers trained in the use of the rattan shield (téng pái 藤牌) and sabre (dāo 刀). The name "Tigers of War" was given by European missionaries, and it does not relate to a Chinese name, as far as we know. The few Chinese references we have found refer to them simply as hǔyī téngpáibīng 虎衣藤牌兵, or téng pái soldiers in tiger uniform.

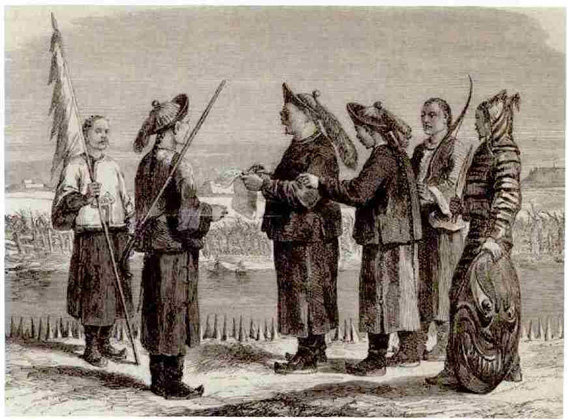

We do not know the origin of this illustration, which shows a téngpáibīng dressed in tiger skins, on the right.

This "Tiger Battalion" should not be confused with the unit called Hǔshényíng 虎神營 ("Tiger Spirit Battalion"), with which it has no relationship. This Hǔshényíng division existed during the mandate of Empress dowager Cíxǐ 慈禧; it was created in 1899 and composed of Manchu soldiers.

Although this "Tiger Unit" of téngpáibīng operated during the Qīng dynasty, there are some precedents in Chinese history of the war use of tiger skins. And, contrary to what some, such as Chamberlin (see below), point to, in a mocking way, tiger uniforms were not intended to frighten human enemies, but horses or other war animals.

Precedents:

The first historical reference we find to this type of strategy belongs to the Spring and Autumn period (chūn qiū shí dài 春秋時代, 771-476 BC). At the Battle of Chéngpú 城濮, it is said that the state of Jìn 晋 placed tiger skins on their horses, which managed to scare away the cavalry of the rival state of Chǔ 楚, which fled in disbandment.

Similarly, during the reign of Emperor Yǒnglè 永樂 of the Míng 明 dynasty, the Duke of Yīng 英國公, Zhāng Fǔ 張輔, used some kind of lion painting on the horses, in conjunction with firearms, to scare off the elephants of the enemy's army.

The first evidence suggesting that tiger uniforms were worn by the soldiers themselves is found in two ceramic figures dating back to the Suí 隋 dynasty (581-618).

These figures depict two horsemen dressed in tiger head hoods, with the animal's skin falling on their shoulders. We know nothing about these mysterious riders, although it is likely that their uniform was used with the same intention of scaring the enemy's horses.

Also during the Míng dynasty, the nationalist hero Zhèng Chénggōng 鄭成功 used a téngpáiyíng squadron in uniforms depicting tigers.

Zhèng is known in the West as Koxinga, romanization of his honorific name, Guóxìngyé國姓爺. Koxinga was a military leader who fought the europeans in Taiwan, forcing the withdrawal of the Dutch, who until then controlled the island.

Zhèng Chénggōng 鄭成功, known as Koxinga.

Koxinga is known to have used his téngpáiyíng against cavalry, attacking the animals' legs with sabres. Historian Tonio Andrade, in Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China's First Great Victory over the West, refers to them as "Tiger Guard", and says they wore iron armor covering the entire body, with tiger heads painted on helmets and shields.

The "Tigers of War" of the Qīng Dynasty

In the years 1685-1686, during the reign of Emperor Kāngxī 康熙, the Qīng empire came into conflict with Tsarist Russia over the territory of Jaxa (known to the Manchus as yaksa; 雅克薩 yǎkèsà in Chinese).

Inspired by Koxinga, he recruited a unit of téngpáibīng, from which it is said that wore tiger skins and heads. These soldiers came from the province of Fújiàn 福建, and were trained and led by a certain Lín Xīngzhū 林兴珠, who had been under Koxinga's command and seen the effectiveness of téngpáiyíng battalions.

A noteworthy story, of which despite having no reliable references from it, circulates in Chinese accounts, tells us that Emperor Kāngxī, who did not develop modern weaponry, reinforced rattan shields to make them more resistant to Russian ammunition, placing "a layer of cotton between two layers of rattan, or a layer of rattan between two layers of cotton" ("藤牌稍薄,双层者加旧棉一层,单层者加旧棉两层,坚固可用"). It seems that this reinforcement could not stop the musket bullets, but it did cause the bullets passing through the shield not to be lethal.

The téngpáiyíng led by Xīngzhū was sent to fight in Jaxa, where it appears that they made some skirmishes successfully against the luó chà 罗刹 ("demons", the name by which the Russians were called in China, and which belongs to Buddhist terminology).

Among these raids is the episode of the battle on the river during the siege of Albazin, in which the téngpáibīng of Lín Xīngzhū attacked the Russian fleet from the water. Chinese warriors immersed in the river naked, covering their heads with rattan shields and armed with their sabres, and stormed Russian boats, killing thirty of their soldiers and holding fifteen prisoners, as well as capturing one of their rafts, without suffering a single casualty. However, tiger skins are not mentioned in this episode.

William Alexander

William Alexander (1767–1816) was a British artist, and primarily responsible for how Westerners perceived tiger soldiers at the time. Painter and illustrator, he accompanied Earl Macartney's embassy to China in 1792, where he made numerous drawings of everyday scenes.

Alexander's drawings had a major impact on the way Europe imagined China in the 19th century, at least until the Opium Wars.

In one of his illustrations, from 1796, entitled "A Chinese Military Post", a group of regular soldiers are seen on the front line, and on one side of the image, in the background, two tiger soldiers can be seen training with sabres and shields.

“A Chinese Military Post”, by William Alexander.

To the left of the image, there are two "tiger soldiers" practicing with sabers and shields.

In Costumes of China (1805), a volume of illustrations with brief textual descriptions, an infantryman is seen dressed in a uniform that mimics the skin and head of the tiger, carrying a rattan shield and a sabre, which he calls "Tiger of War", clarifying that this is the name given by European missionaries to these warriors. In his description, Alexander makes a brief mention of the uniform, but does not clarify who these "Tigers of War" were.

"A Chinese Soldier Of Infantry, Or Tiger of War",

from William Alexander's illustrations book "Costumes of China".

The accounts of "Tiger Soldiers" reappear again during the First Opium War (1839–1842). The Qīng armies were defeated over and over again by British forces. Emperor Dàoguāng 道光 used a contingent of tiger-clad téngpáibīng to face the enemy.

In 1842, the Manchu prince Yìjīng 奕經 used a contingent of seven hundred "Tiger Soldiers" from Sìchuān 四川 in the battle of Níngbō 寧波, with fateful results.

Similarly, in Dìnghǎi 定海, the British killed several hundred "tiger soldiers" with their firearms, while they suffered only one casualty. Tiger uniforms don't seem to play any decisive role in this encounter. These could work against horses, but not against an army that did not rely on animals.

Tiger soldiers were also used in the defence of Xiàmén 廈門 in August 1841, in the face of the British attack.

British Officer John Eliot Bingham's account mentions these soldiers as dressed in striped uniforms and caps with small ears. It is also said that the resistance in the taking of Xiàmén was rather scarce. We even have a graphic depiction of this battle, in an illustration by Michael Angelo Hayes and James Henry Lynch, with the "Tigers of War" included in it.

“The 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot, At the Storming of the Fortress of Amoy, August 26th 1841”,

by Michael Angelo Hayes y James Henry Lynch.

Amoy is the name by which the British knew Xiàmén 廈門.

After these incidents, we do not hear again about the combat action of this contingent, which became the laughing stock of the dynasty, and the object of mocking by some European observers.

¿Phantom soldiers?

Alicia Little (1845–1926), better known as Ms. Archibald Little, was a British writer and women's rights activist. Married to a merchant, she lived and wrote in China for some time.

In Intimate China: The Chinese as I have seen them (1899), Little doubts the existence of the "Tigers of War", and claims to have heard that it was not a real unit, but a "phantom" group, by which some corrupt officers pocketed money. It is true that at that time it was not uncommon for certain officers to enlist fictional or "phantom" soldiers, whose pay was issued by the government and which ended up in the pocket of those who supposedly led them.

The latest clues about the "Tigers of War" are provided by Wilbur J. Chamberlin, a reporter for the American newspaper New York Sun during the Boxer Rebellion. In Ordered to China: Letters of Wilbur J. Chamberlin, a collection of letters written in 1900 and published in 1904, Chamberlin claims to have crossed paths with a tiger soldier who caught his eye. He says he belonged to the "Tiger Brigade" of the Imperial Army.

According to him, the soldiers of this brigade, of which he mocks, are placed on the front line, onto hands and knees, roaring to frighten the enemy. Their uniforms are an imitation of the tiger's skin, not real skins.

We must understand Chamberlin's mockery in the context of Western victories over China, linked to the crumbling of the country's romantic image that had been part of the European imaginary during the previous century.

Illustration from a military manual (兵技指掌圖說 bīng jì zhǐ zhǎng tú shuō),

showing a group of téngpáibīng dressed as tigers.

On the right it reads:

"The training of the téngpái requires a flexible waist, fast footwork,

holding the téngpái in the left hand, holding the sabre in the right hand,

using the téngpái to scare the horses, hiding the sabre to attack the enemy,

rolling the téngpái, using hands and eyes together to defend the body and defeat the enemy;

skillful training requires using powerful attacks against the cavalry.

This is the way to practice with the téngpái."

Conclusion

Despite the lack of reliable references identifying the téngpáibīng of Lín Xīngzhū as "Tiger Soldiers", these definitely made their appearance during the Opium War. However, it is precisely in this historical context that tiger skins or uniforms were less useful as a military strategy, so we must understand these as a symbol of identity, and not much as a practical element.

These téngpáibīng, no matter how well-trained they were in the use of shield and sabre, were already almost an anachronism in the war context of their time. Hence their little effectiveness in combat.

As we already mentioned in the article The Rattan Shield, téng pái used to be decorated with drawings of tiger heads, due to the association between the word tiger, hǔ 虎, and the word protect, hù 護. It is possible that this association was expanded to end up applying itself also to the uniform and not just to the shield.

In any case, the "Tigers of War" are a mysterious contingent of which we lack reliable references today. Let's hope we have more data in the future, and let everyone draw their own conclusions